When I was between the ages of 8 and 10, I used to stack

pillows up on the end of my parent's living room couch. I would then dress up

in my Bears uniform and dive over the pile like a running back. Other times on

Sunday mornings, I would don the same uniform and run around the back yard,

emulating a certain goose-stepping leg kick I would watch on television later

that day.

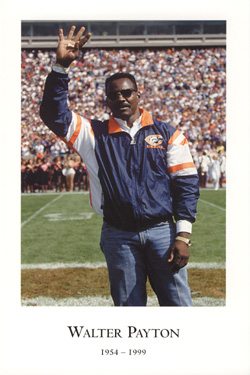

That person I was trying to imitate was Bears running back

Walter Payton, who was then a 26 year old NFL star. On this I reflected as I

sat in Soldier Field on November 6, 1999, for the late Payton's public memorial

ceremony. I was not ashamed to tell people how I cried a lot that week, not for

an athlete that I used to worship for his athletic skills, but for a wonderful

human being that was taken from this life far too soon. I did not, and still do

not, call athletes my "heroes" because of their athletic ability. But that

week, thousands of young men like me lost a part of their childhood with Walter

Payton's passing.

Growing up

Walter Payton was born in 1954 in Columbia, Mississippi, in

the heart of the racially-charged South. Edward and Alyne Payton had three

children, Eddie, Walter and Pam, who entertained themselves growing up in the

woods around the small town, before the likes of Playstation and television

were the staples of American youth. Along with exploring, fishing, and hiking,

Eddie and Walter became involved in every sport they could. During the summers,

Alyne would have a pile of topsoil dumped outside the house, and the boys

worked all summer long to move that pile throughout the yard, little by little.

Alyne would say she arranged for the dirt as a project to keep the boys off the

street and out of trouble, and it worked.

Walter played football his first three years at all-black John

Jefferson High. His senior year, the decision was made to integrate Columbia

High, and Walter made the transition seamlessly. One teammate remarked that the

racial integration issues didn't bother them; that being racist was for the

adults.

After high school, the options for a black athlete in the

south were limited, even in the late 1960's. Though schools like Alabama,

Mississippi and Louisiana State began recruiting blacks, there were more

opportunities for players like Payton to head to California or Big Ten schools.

Most, like Payton, chose to stay closer to home at traditionally black schools

such as Jackson State, in Jackson, Mississippi. Thus, Walter chose to follow

older brother Eddie there. Eddie had been a star there, and would head to his

own NFL career as a kick returner with Cleveland, Detroit, Kansas City and

Minnesota.

At Jackson State, Payton excelled and finished fourth in

Heisman Trophy voting. Many believed he would have won, had he played at a

school with any amount of notoriety, which Jackson State lacked. Walter

excelled not only in athletics, but in academics as well. He even made a

national appearance on Soul Train, performing the "Cock Walk", a dance move he

created. By early 1975, the big city and the NFL beckoned.

Chicago

With the fourth pick in the 1975 NFL draft, the Bears selected

Payton. Chicago's running game hadn't been the same since Gale Sayers'

retirement due to injuries in 1971. It remains a mystery how Payton lasted

until the fourth pick until this day. Taken before him were QB Steve Bartkowski

by Atlanta, DT Randy White by Dallas, and G Ken Huff by Baltimore. It was

recounted later by then-Cowboys assistant Mike Ditka that Dallas engaged in

heated arguments for Payton leading up to the pick, but relented and took

White.

Payton's illustrious career began with a less-than-stellar

performance. In his first NFL game, Walter carried the ball eight times for

zero net yards. Although 1975 began with a performance that didn't merit

writing home about, the season finale did. At New Orleans, Payton ripped off

perhaps the best touchdown run of his career, finishing with 134 yards on 20

carries, the Bears' best rushing performance since Sayers resided in Chicago.

Walter finished his rookie season with 679 yards and seven touchdowns, the

lowest total of his football career. Also, the biggest letdown of his career

occurred that season, as Payton was held out of the only game he would miss in

13 seasons. Not because he couldn't play, but because the trainer wouldn't let

him. But the best was definitely yet to come.

Mid-Career

Payton topped 1,000 yards and scored 13 touchdowns in 1976,

and was voted the NFL's Most Valuable Player in 1977. Chicago went to the

playoffs after the '77 season, which also featured a 275-yard game by #34,

which stood as the best single-game performance in NFL history until it was

surpassed by three yards in 2000.

It was during the years 1976-1981 that the Bears became

defined by Payton. Payton was the Bears, and jokes circulated that their game

plan was as simple as Payton left, Payton right, Payton middle, punt. Although

an asterisk can't be placed next to Walter's career statistics, it must be

remembered that during the bulk of his career, he was running behind patchwork

offensive lines. Many highlight films feature Payton running off-tackle to the

right, stopping and ending up sweeping to the left, avoiding being trapped for

a loss in the backfield. Sweetness, which became Payton's nickname early in his

career, rushed for over 1,000 yards in every season from 1976-'81, earned the

NFC rushing crown in 1979, and made the Pro Bowl after each season.

Though 8-8 and 6-10 seasons in 1981 were no fun on the field,

Payton helped make life fun in the locker room by becoming the club's biggest

joker and purveyor of practical jokes. Some notable pranks Sweetness loved to

pull were sneaking into the locker room before everyone else to lock the entire

team out in the snow, taking over the Halas Hall switchboard to answer the

organization's phone calls, and repeatedly calling Matt Suhey's wife in a

high-pitched voice, pretending to be a girlfriend. Perhaps this "Sweetness

spirit" was the underlying fuel to the charismatic Bears that would take the

field a few years down the road.

Ditka Arrives

Most historians trace the turning point in Payton's career,

from being the best player on a losing team, to the best contributor to a

winning team, to the arrival of Mike Ditka as Chicago's new coach in 1982. In

Ditka's first speech to the players in the Spring of 1982, he stated that his

team would be going to the Super Bowl, and some would be there and some

wouldn't. This was the first statement of confidence the team had heard from a

leader in some time, and Ditka intended to back his words up. Along with

bringing a winning attitude, Ditka, along with General Manager Jim Finks, for

the first time started assembling a supporting cast that would ensure Payton's

success. An already tough defense was bolstered with such players as Richard

Dent, Dave Duerson and Wilbur Marshall. The offense, once featuring Payton as

its only weapon, added gambling Quarterback Jim McMahon, reliable and speedy

receivers Willie Gault and Dennis McKinnon, and assembled a dominating

offensive line, featuring Jim Covert, Mark Bortz, Jay Hilgenberg, Kurt Becker,

Tom Thayer, and Keith VanHorne. After 3-6 and 8-8 seasons in 1982 and 1983,

Chicago felt they were primed for a real run at the postseason in 1984.

In addition to dominating the NFC Central by the middle of the

'84 campaign, Walter Payton was poised to break Jim Brown's all-time rushing

record in the season's sixth game. Sweetness broke the record early in the

third quarter on a toss left, and after a few celebratory high-fives, in his

typical fashion he urged everyone off of the field to allow the game to

continue. After the game, Payton dedicated his achievement to all the athletes

that didn't have the chance to achieve their goals-men such as the late Brian

Piccolo. Injecting his typical playful antics into the day, Payton finished his

postgame press conference by speaking to President Reagan and asking him to

give his best regards to Nancy.

The '84 Bears finished the regular season 10-6, and won their

first postseason game since 1963 at Washington. During that game, Payton threw

a touchdown pass to TE Pat Dunsmore, adding to his long list of achievements.

The following week, Chicago lost the NFC Championship at San Francisco, and TV

cameras showed Payton sitting dejectedly on the bench. After the game Payton

voiced his sorrow to the press. His team had come so far, and tomorrow is

promised to noone, so who knew if he'd get his shot again at the elusive Super

Bowl ring.

1985

That shot came during the ever-celebrated 1985 season. Payton

made perhaps the least-heralded but best block of his career when he leveled a

blitzing Vikings linebacker at Minnesota. That pancake allowed Jim McMahon to

complete the first of three TD bombs in Chicago's comeback victory. The next

week, Payton threw a TD pass to none other than QB McMahon in a 45-10 thrashing

of Washington. Despite the team losing to Miami after a 12-0 start, Payton set

the NFL record for most consecutive 100-yard games at 11. In that game, it was

reported that McMahon changed plays sent in from Ditka to ensure Payton's place

in the record book. The day after the loss, Payton took the starring role in

the Super Bowl Shuffle, a recording that went gold and remains the anthem of

Chicago sports. Finally on January 26, 1986, Payton reached the pinnacle of

sports greatness as Chicago defeated New England 46-10 in the Super Bowl. If

teammates were asked who the victory would be dedicated to, unequivocally they

would say Payton in tribute to his outstanding career and dedication to the

sport. However, the victory ended up being bittersweet for Sweetness. Despite

Chicago rushing for five touchdowns, Payton wasn't given the ball to score, as

New England scripted their entire game plan to stop him. Ditka later called

this his greatest regret in all his career-not getting Payton into the endzone

in football's biggest game. While expressing disappointment, Payton later let

bygones be bygones in the usual Payton tradition.

Sweetness continued to carry the Bears through 1986, during

which the team looked to be a lock for another Super Bowl championship. Despite

setting defensive records throughout the '86 campaign, quarterback problems

spelled doom, and Chicago lost their opening playoff game to Washington. In

1987, Payton announced that year would be his last. Sweetness split carries

through the season with his heir apparent Neal Anderson, and was given a

tearful sendoff in his last game at Soldier Field. Chicago again exited the

playoffs at the hands of the Washington Redskins. Following the loss, which

ended with the quintessential extra effort on a failed run by Payton, Sweetness

sat at the end of the Bears bench with his head in his hands, trying to take in

every bit of his Hall of Fame football career.

Life After Football

In 1988, Payton joined the Chicago Bears Board of Directors.

Later, he would pursue ownership of a new NFL franchise in St. Louis, a plan

which would ultimately not come to fruition. After that, he formed a CART

racing team with partner Dale Coyne, and survived a spectacular collision while

racing at Elkhart Lake in 1993. In 1996, Walter Payton's Roundhouse, a

restaurant and brewpub featuring the Payton Hall of Fame, was opened in Aurora,

IL. Payton's son Jarrett started high school in 1995, and stunned the public by

deciding to play soccer over football at St. Viator High School in Arlington

Heights, IL. Payton supported the decision fully, but Jarrett made the switch

to football his Junior and Senior years. In late 1998, Walter and his wife

Connie began helping Jarrett entertain scholarship offers and were primed for a

public announcement regarding where he would attend college.

Illness

Sadly, instead of making a happy announcement in early 1999,

Payton faced the media in Chicago to announce that he had been diagnosed with

PSC (Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis), a condition that may lead to cancer of

the bile ducts in the liver. Suddenly the lines that Walter used earlier in his

career, such as "Never Die Easy", and "Tomorrow is promised to no one," struck

close to home. Payton had been feeling sick since the middle of 1998, and was

diagnosed at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. Walter's appearance had some

people wondering what could be wrong for several months, but in his typical

fashion, Payton attributed his gaunt appearance to preparing for a marathon.

After that February day, the city of Chicago collectively held their breath and

lent their prayers to their greatest sports figure and his family.

Payton spent the remaining months of his life underneath the

public radar, as he always wanted to. Outside of an appearance in April at

Wrigley Field to throw out the first pitch at a Cubs game, Payton avoided the

limelight. The only public updates on his condition were from his family, who

occasionally spoke to the media optimistically. Payton had been put on the

waiting list for a donor liver, but would not be moved up the list due to his

notoriety. What was not disclosed by the family was that during the Summer of

'99, it was discovered that his cancer had spread, and the likelihood of him

qualifying for a transplant was fading. Payton spent his remaining time with

his family and close friends such as Mike Singletary and Matt Suhey. During

October of that year, rumors and speculation ran rampant in the press about

Payton's condition, until November 1st, when it was announced he had passed

away.

His Legacy

Chicago went into full-scale mourning that Monday evening, a

grieving that lasted the entire week. Tears were shed by millions like me that

grew up emulating the great running back, as well as those that didn't watch

football but remembered him taking the time to shake their hand and say hello.

John Madden, Mike Ditka and others eulogized Payton at his funeral, and

thousands of fans and the '99 Bears team showed up at Soldier Field that

Saturday to celebrate his life. The next day, the NFL held a moment of silence

at all games, and the Bears upset Green Bay on a last-second blocked field goal

by Bryan Robinson. In one of the few utterly religious moments of my life, I

believed that Walter Payton actually pulled some strings from heaven by

arranging for the miracle finish.

Perhaps Payton's greatest achievement in his passing remains

that organ donation in Illinois has skyrocketed since the announcement of his

illness. Connie Payton continues to operate the Walter and Connie Payton

foundation, which among other things donates Christmas toys to thousands of

underprivileged children. And despite his untimely passing, Walter Payton's

kind, compassionate, and humorous character will live on in the hearts and

minds of people around the world for eternity.

walter payton biography

4/

5

Oleh

Agus Prasetyo